In December 2019 I was in a group of Griffith Film School master’s degree students who travelled to Hungary and Latvia to create an immersive short documentary film using 360 virtual reality (VR) technology.

Sorella’s Story, written and directed by Peter Hegedus, associate professor and filmmaker at Griffith University, showcases re-enactments based on photos of atrocities committed against Jewish people during the Holocaust in Latvia.

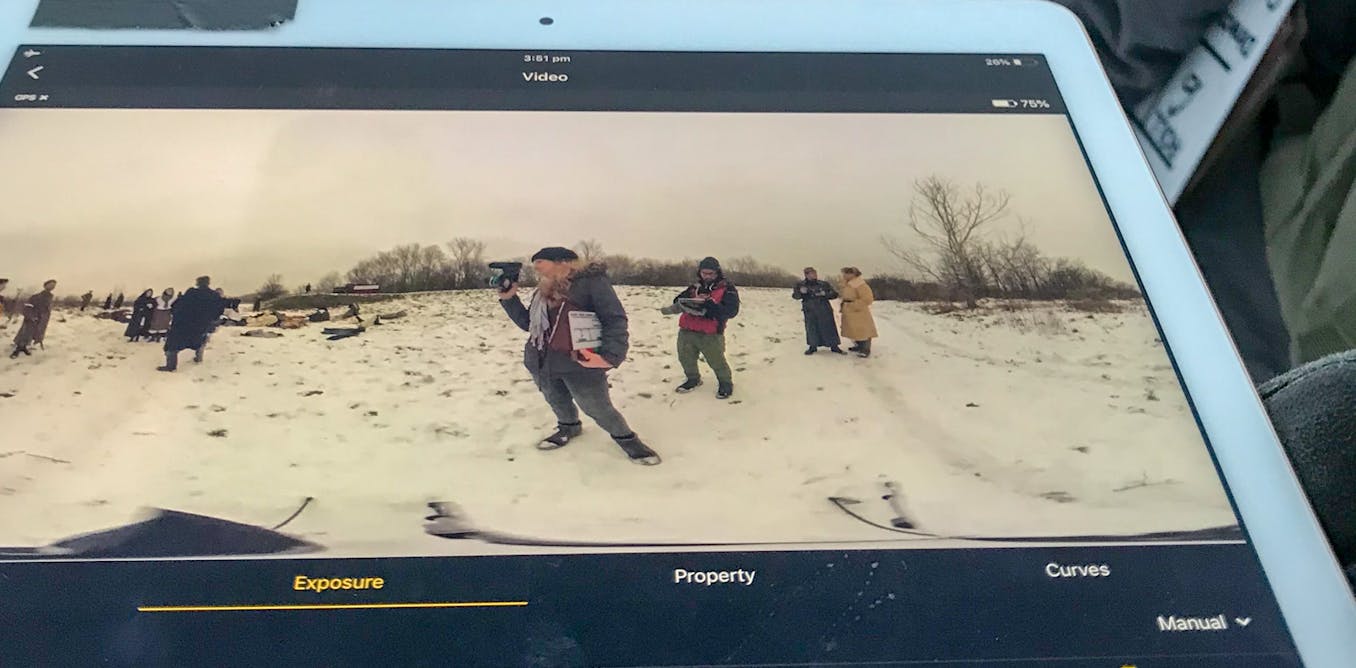

The shot schedule was ambitious. We had five exterior scenes to be shot in only a few hours because of the limited daylight. We had a crew of about ten people.

I was director of photography and the only cameraperson. A daunting task in any filmmaking situation, it was made tenfold more challenging by being a 360 project that no one on the crew had experience working with.

Read more:

The air we breathe: how I have been observing atmospheric change through art and science

New technology brings new challenges

Viewed through virtual reality lenses, 360-degree films offer the viewer an opportunity to watch a video from all angles.

Unlike traditional cameras with a single lens, our 360 camera looks like a soccer ball, with six small lenses placed throughout the body.

It was a new technology for me and I was curious to see how it was going to change our approach. For example, the six lenses film simultaneously, so the operator and crew need to ensure we have a safe spot to hide to avoid being caught in the frame.

Author provided.

The distance actors appear from the lens is especially important in 360 filming. This is because the images are “stitched” together in post-production. If the subjects are too close to the lenses, the images can’t be combined to create the appearance of a single shot.

After our test shoots, we gave actors marks to hit in and out of frames and the maximum and minimum distances they could be from the camera. These modifications enabled us to capture the action from all 360 angles.

We needed precise blocking and rehearsed co-ordination between actors and crew to capture the entire scene. Every time a scene was recorded, the director would call action, and the sound and camera crew would have a few seconds to run and hide out of frame. Only then would the actors begin to move.

360 inherently brings with it technical challenges, but Sorella’s Story had the compounding issues of weather, a remote location and myself as a cinematographer without a crew and limited time to learn the technology.

Shooting plan

Prior to filming a conventional project, directors and cinematographers break down the script into a shot list – a written breakdown of every shot that will be undertaken – and storyboard, visually symbolising those shots through illustrations or sketches.

Both tools help the filmmaking process and ensure the creative vision is realised on set.

Storyboards are less important in 360: you aren’t considering how different angles will be used in a shoot, and there is much more spontaneity in the actors’ movement. There is so much action to capture at once storyboards would just confuse the issue.

Instead, a shot list and script were followed in some moments, but were used as only a guide.

Author provided.

Obstacles and problem-solving

December is one of the coldest months of the year in Budapest, Hungary, with average temperatures of no more than 1°C. At this time of year the days are short, the nights are long, and icy weather conditions are expected. Those conditions brought another challenge: the battery life of electronic devices.

I quickly learned cold weather drains the battery. I tried to reduce cold exposure on the camera by covering the camera with my beanie, with limited success. Battery life that was usually two hours was down to 20 minutes.

Because of the limited budget, we had only two batteries for each device. Ideally, we would have one battery in the camera and the other plugged into the charger.

However, we had no power supply on set. Every time a battery ran out it would be 10 minutes to the nearest power supply, plus at least 30 minutes to recharge.

Jemma Potgieter

Shooting in this cold climate, ensuring I was invisible on set and maintaining the delicate balance of the distance of actors from the camera demanded a complete re-evaluation of my filmmaking approach. It forced me to be agile in my workflow and engage in real-time problem-solving.

Despite the inherent challenges, working on this project provided me with invaluable experience in this cutting-edge technology. With the current interest in immersive experiences, 360 cinematography has a part to play in cinema’s future.