Nora learns from a mate that Javo likes heroin, though he seems to have kicked it; the mate is the girlfriend of Nora’s housemate, and in the anything-goes manner of the time, Javo is soon hanging out with Nora and Martin, enough that Javo can ask Martin how “together” they really are, and relay Martin’s evasive response straight to Nora – a canny move for such a cruisy guy.

Soon, she’s taking him to an art show that she has to cover for the small, busy alternative paper for which she writes reviews. Afterwards, she asks him if he’d like to stay the night. “That would be good,” he tells her, and it’s on.

MIFF

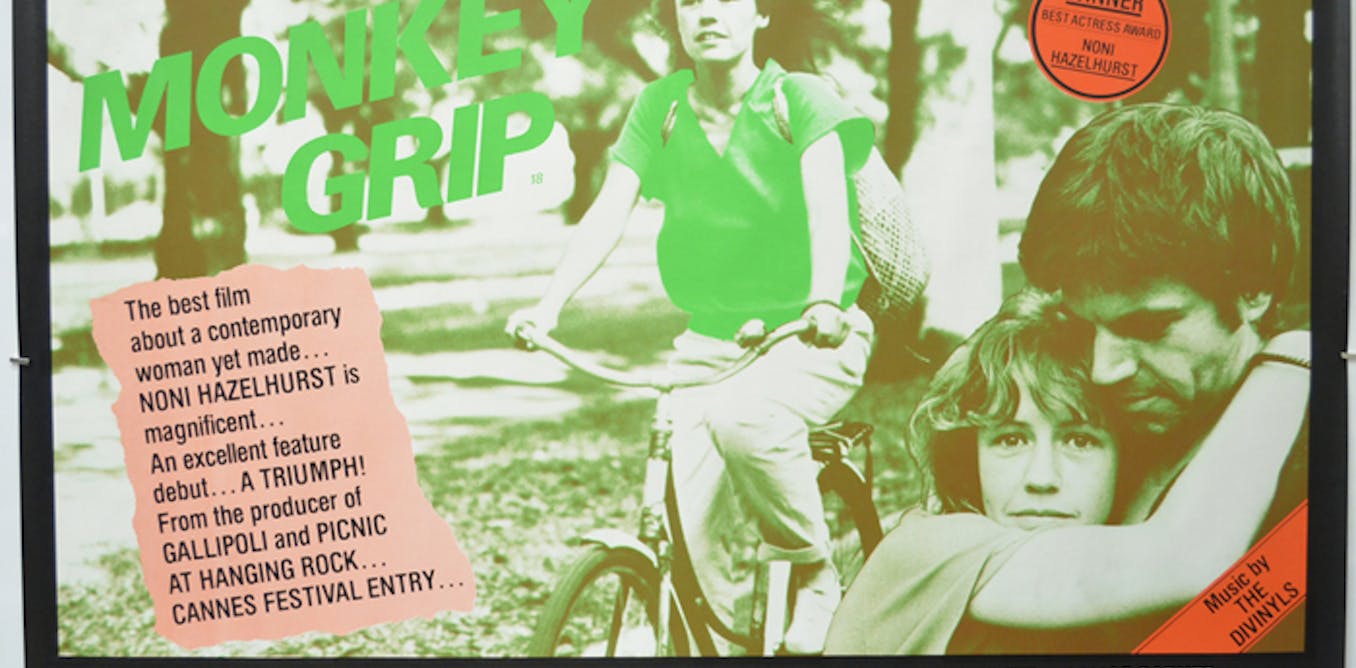

In the morning, Nora’s 11-year-old daughter, Gracie, finds out; Martin finds out. After Javo heads off, Nora relaxes in the kitchen and says, “I suppose I’ve done it again” – the wrong thing, the wrong man – but the story we’re talking about, of course, is Ken Cameron’s Monkey Grip (1982), and the casting of Noni Hazlehurst is one of its great coups.

Resignation, pleasure, self-satisfaction, concern: it’s all there in the delivery, and it all takes a back seat to a wonderful feeling that it doesn’t matter much at all. She supposes she’s done it again, and you may now grow aware of a disquieting question that is interesting to this movie the way a mouse is interesting to a cat.

Maybe understanding the implications of what you’re doing has little to no bearing on whether or not it’s actually done? And then the inverse – you can be wise enough to know what’s happening to you and have it happen anyway. This suspicion becomes unbearable as the film goes on. Nora’s carefree nature, which can be cruel but is rarely nasty, lifts the viewer and carries them over the movie’s darkest parts, but there’s always the sense that something irrevocable is happening, a little bit past the line of sight, a little way out of control.

Making a novel into a movie

The film is based on Helen Garner’s 1977 novel, and Garner and Cameron are listed as co-writers. On the indispensable website Ozmovies, where the Monkey Grip entry splices an interview with Cameron by Peter Malone and an account of Cameron’s DVD commentary into a narrative of how the screenplay was written, Cameron explains that he cut up and re-pasted the novel, typed it up “so that it resembled a movie”, then finessed the adaptation in constant conversation with Garner; he has a collection of letters in which she suggests solutions and scenes.

Garner says on the DVD commentary that she saw 14 or 15 drafts of the script, and then was there for the filming because Nora’s daughter, Gracie, is played by her own daughter, Alice, who is a sharp presence through the film, cheery and watchful, and possessed of slightly eerie wisdom.

Garner disliked the casting of Colin Friels as Javo, telling The Age’s Peter Wilmoth in 2008, “I just can’t believe they cast Colin Friels as the junkie. [. . .] He was so healthy, a great big bouncing muscly surfing guy.” We all know people like Javo – if not the heroin, then the sulky mood – and it’s true that they’re not Colin Friels.

But I think of a point that a friend once made about a different kind of story, where two impossibly hot people have a meet-cute on a tram. That doesn’t happen in real life, someone at the time complained. But there are people in the world who look like that, my friend explained; when they hook up, it’s often with each other, and it has to happen somewhere.

If Friels’s Javo is not realistic to the story, then neither, perhaps, is Hazlehurst’s Nora, and you have to have someone like Friels to make the viewer believe that someone like Hazlehurst would give him the time of day. Monkey Grip is a movie, and it has to have some glitz. They have to hook up somewhere, and they hook up here.

Umbrella Entertainment

Sex was an issue for this film. At first, nobody liked it, neither the distributors, nor “most of” the Australian Film Commission, which, speculated producer Patricia Lovell, saw it as pornographic. Stratton had interviewed Lovell for his 1990 book The Avocado Plantation, about the turbulent economics of the 1980s in Australian film. The story of Monkey Grip’s production is harrowing. It almost found funding, but “fell over for lack of $150,000”.

Lovell moved on and produced Gallipoli instead; by the time tax breaks made production more viable, other costs had gone up, so it was still a struggle to fund. When it finally got off the ground, some new funding problem meant that it looked like production might delay for two weeks – sending Lovell to hospital, where she spent 48 hours under sedation from nervous exhaustion.

When the film was done, Lovell heard that Gilles Jacob, director of the Cannes Film Festival, had been told “by someone in authority” that “the Australian government would not be pleased if Monkey Grip competed at Cannes” (though it did). Lovell screened the movie for three distributors in Melbourne, all of whom turned it down; one told her, “I loathed it.” Finally, Lovell distributed it herself, and after the first week’s takings offered proof of its heft, it was picked up officially by Roadshow.

Lots of films are incredibly sexy or incredibly sexual (dark, yearning, weird); Monkey Grip is both. It shows the parts of sex that are all about desperation, habit and distraction as much as those that are about intimacy, spontaneity or fun.

The first time Nora has sex with Javo is full-on, but first it’s so tentative that you think it might not happen; they get under the covers and at first you think they might just go to sleep. As soon as it’s happening, you realise that it was silly to think it might not. The eyes are closed, the clothes are off, the facial expressions work very hard; there’s some finger-sucking where the camera doesn’t cut away, and a kiss that’s more sexual than the finger-sucking.

Cameron told Stratton:

I had no problem with the actors during the filming of those scenes. I felt it was worth going all the way with them, and I was young enough not to have hang-ups. The atmosphere on the set was a bit funny: in the end, I had the entire crew, myself included, rehearse naked . . . we all believed in the novel and the film, so we felt those scenes had to be done that way.

It’s great, and sex reappears throughout the film as something that’s both absolutely normal – enmeshed in work, time, reading, eating sandwiches, meeting deadlines, having daughters, moving house, writing lyrics, being in bands – and something that’s like Javo: on a spectrum between consuming and impossible.

On smack

After Javo behaves oddly at a party, he says to Nora, “You just don’t get it, do you?” When he’d told her he was “stoned” earlier, he meant he was on smack. Nora smiles and kisses him. Javo overdoses. Nora visits him in hospital, where Javo is smoking. He looks at an old man across the room and says, “Jeez, old people give me the shits.”

Abebooks

Javo comes over to Nora’s share house and finds her in the shower and decides that she will be the one to give him outpatient care. Someone who knows how to inject penicillin comes over to show her how it’s done. Nora gives the injection; Javo is upset. They make jokes about the penicillin injection that are really jokes about junk; Gracie grabs the needle and says, “Don’t do it – you’ll get hooked!” All laugh. Everything in the house appears to settle down. Javo becomes part of the family, presiding over the children Nora lives with and the sharing of gifts.

And then one day Javo’s gone. First there is a false bottom, which presages those to come. He’s gone, and Nora finds him again, in a kind of drab bohemian lair, a large, dark, brick building with an arched window, where he gets to gesture at a traumatic origin. He has sex with Nora. He says – or sort of says; the line is fed by Nora – that his father is the reason women “never hit the mark”.

That night, Nora wakes up and Javo isn’t there. She finds him in another room, in the middle of shooting up, which he finishes doing despite her presence, half meeting her eyes. And then he’s really gone; he’s off to Singapore, with Martin (the guy Nora was seeing at the start – played by Tim Burns). Javo sends Nora a postcard. He wrote it on the plane, so there’s nothing about the trip itself. The world has swallowed him up.

The seasons change; Nora’s place of residence changes. She hears news in the winter that Javo is in Bangkok, in prison for stealing sunglasses (also with Martin). She sends him letters daily. “I miss him a real lot,” she tells a friend she’s hooking up with. “Like a piece of glass stuck in your foot,” the friend suggests.

And then, one sunny day, he’s back – in a garden full of hanging ferns and staghorns, Nora’s new, less-ramshackle share house. They go inside; she touches his face; they have sex slowly. “Now that he was back all the splinters of my life made sense again,” narrates Nora.

But straight away, there are new complications – pasta, women, alternative theatre. Nora takes Javo for coffee and gnocchi with her pension cheque, and Javo ruins it by going to talk to another woman under the obvious pretext that he wants to see what kind of cigarettes they’ve got behind the counter. The woman is Lillian (Candy Raymond), a co-star in a play he’s acting in, and he lurks on the other side of the restaurant chatting her up while the waiter brings the meals out to Nora.

“I mean, she’s too much,” Javo tells Nora; but Nora “feel[s] like she’s lining you up”. Later, the play is staged, in an awful and effective little scene, with Javo as the greasy bartender in a shiny vest, while Lillian is playing a “sight for sore eyes”, a “babe” in a silver slitted dress.

He has to throw up, he leaves the stage but doesn’t quite make it, getting as far as a prop piano bench. Nora runs down from the audience to tend to him, and he keeps speaking his lines while he’s sick.

A third-act feeling

Now there’s a third-act feeling; things begin to escalate. But part of what makes it so hard to watch – so like relationships you’ve seen people have, relationships you’ve been in – is that there aren’t any climaxes or moments where peace is restored, there’s just peaks that mean nothing, moments of understanding that distract from other problems, resolutions that will probably be broken.

The Movie Database

Garner told Wilmoth that Cameron found her novel hard to adapt for film because

it hasn’t really got a filmic structure. It’s like a long-running TV series . . . it just starts and it goes on and on and eventually it stops.

The film mirrors the novel, which mirrors life, yes, but it also mirrors Javo, whose personal magnetism is all the more striking because the rest of him is staggering, exhausting. Cameron cast him after Doc Neeson, frontman of the Angels, dropped out and Cameron saw Friels at the Sydney Opera House playing Hamlet. For all his gravity he’s also disappointing and ordinary (“Jeez, old people give me the shits”); the story is never allowed to settle around him.

He creeps into Nora’s bed for comfort like a sick kid would. She holds him and kisses him. A needle is left out on the dining room table, in the middle of a household scene where the children are hitting Nora in the head with their dolls and asking her to make them cups of Milo.

“I want to stop,” says Javo, “but I can’t do it now. I can’t stop while the play’s on . . . I can’t perform when I’m coming down.” Nora understands. “When the play’s finished I’ll get off it and we’ll go away somewhere, go up north.” They’ll go to Sydney, see some friends, go to the beach, get a tan. He’ll go cold turkey. “I’m sick of the junk,” he says.

Cut to Javo playing harmonica in the passenger seat of a Mack truck being driven by a stranger, Nora and Gracie in the back. Soon, they’re at a diner just outside of Sydney, facing the kinds of problems faced by families on Australian road trips. They can’t order pies because the diner microwave’s turned off. Perhaps things are going to be all right.

Filming Sydney as ‘a pretty good Melbourne’

Although Cameron seems sheepish about the fact that Monkey Grip was filmed largely in Sydney – he explains in the DVD commentary that he was based in Sydney, as were Lovell, the DOP and the production designer, so by the time casting was done (in Sydney) and they’d secured funding, “we’d dug a big hole for ourselves in Sydney” – it’s a great joke of the movie that it does a pretty good Melbourne.

“I would have loved to have made it in Melbourne,” says Cameron, beyond the one week of exteriors he was able to film: “it’s the plaster that you see outside the window, it’s just all sorts of tiny things that you can’t reproduce”.

But when Nora rides her bike down a wide, leafy street, it feels like a suburb of Melbourne where you just haven’t been. Because the film is iconic to Melbourne (as is the novel), it’s satisfying that this seems to have no impact on viewers, as little as knowing that Rear Window was filmed in LA. It undercuts the seriousness that forms around iconic things; it makes it easier to see the thing itself.

When they get to Sydney – which scenes were also filmed in Sydney – the house they stay in is all pink light. The bed is “pre-warmed” by a dog. ‘What a good idea!’ says Javo when Gracie jumps in the bed, and they cuddle up together. It’s holiday time. With a clean shirt, Sydney light, and a comb run through his hair, Javo is transformed into a man on the upswing. Nora catches him trying to take money from her purse while she’s napping and says “Jeez, you’re good-looking.” He asks if 20 bucks is okay; he’s “just going to see some friends”.

While he’s out, Gracie consults the I Ching – big part of the novel, small part of the film – about the likelihood that the three of them will be going as planned to Manly tomorrow. The universe responds and says “don’t count on it, sister”. Nora asks Gracie what she thinks of Javo, who acknowledges that he’s a junkie, which of course has its problems, but, “You should be nicer to him, and leave him alone, that’s what I reckon.” When he finally comes home, Nora finds him in the kitchen, suspiciously going to town on a baguette.

“This was supposed to be a holiday,” says Nora. “What are you doing, what do you want?” He says, “I want some Vegemite,” and it’s all downhill from there. He converts a fight about doing smack and making empty promises into a discussion about whether or not he’s understood. If she understood him, would she like him? A good question at the wrong time.

Later on, in bed, he says, “I do this over and over. Whenever I get something good, I destroy it.” But just as he’s really exhausted your patience (you lose patience with both of them), the film finds something new in the couple, which is one of the pleasures of the looser, TV-like structure, where characters don’t have to change and grow; they can surprise you with qualities that disappear, then emerge anew, as if shuffled.

When it’s obvious that they’re done with each other, generosity becomes possible. They have a tender disagreement about which of them is going to leave the trip early and go home to Melbourne. It’s him. They kiss. As he rides away in the cab, he plays a little riff on his harmonica and gifts it to Gracie. Gracie and Nora catch the ferry to Manly. “You’ll get over it,” Gracie advises Nora. The ferry’s nice at night, she observes. While Javo has been happening to Nora, Gracie has been growing up. How often do you get to see this kind of thing on film, the child turning casually into the adult?

In The Avocado Plantation, Stratton points out that Hazlehurst as Nora in 1982 seemed like it would herald a coming age of complex roles for women actors, which the rest of the 1980s turned out to largely squander. He also mentions Wendy Hughes’s role as Vanessa in Carl Schultz’s excellent 1983 movie Careful, He Might Hear You, another adaptation of a well-loved Australian novel.

I got chills when Nora and Gracie went on the Manly Ferry; at the end of Careful, He Might Hear You, Vanessa, who’s a snob, decides for once in her life to cross the Harbour on the Ferry, gets into a collision, and drowns. Over in Melbourne, Hazlehurst’s Nora puts on her lipstick and decides it’s time to give her life a little TLC. Her metaphor is a tub that’s been draining towards Javo; now it’s time to put the plug back in.

She goes to a gig. (It looks like The Corner, but I’m sure it’s in Sydney.) One of the odd surprises of the film is that Chrissy Amphlett, Divinyls frontwoman, plays a muso in Nora’s circle named Angela; at the gig, she plays ‘Boys in Town’ from start to finish, but with actors playing the band (the rest of the Divinyls turned down roles in the film).

Nora’s hair is slicked down and tied back; she’s wearing a sleek, feathered dress. She cuts loose, dances, laughs with friends; she reconnects with former housemate Clive (played with warmth by Michael Caton). Nora’s world remains spiky and young but it’s comfy without Javo. Soon, she’s writing in front of an open fire. She’s writing on a tram. She writes a short story addressing her feelings towards Lillian and doesn’t think there’s any particular reason to show it to her before publishing. Her life changes again. She moves house again. There’s the sticky business of telling her housemate, but these things are there to be dealt with.

“I just want it quite clear,” she tells the man she’s moving in with, “that we’re not moving into this house as a couple.” She reads books; she looks up words in the dictionary. Around her, children squabble. The framed picture of Virginia Woolf that Nora transports between residences assumes its place above the new workstation, perpetually stately and sentinel. Then, once again, there he is, in a striped shirt of thin fabric and a ragged, rather fashion-forward open seam. “You look great,” she says. “What happened?”

It’s Javo’s softer side. They go up to her bedroom. He sits in a sunny chair. “I’ve been having a really good time these days,” he says. “I’ve been knocking around a bit. Seen Lillian a couple of times.” Nora lies on the bed looking deeply unimpressed. Unprompted, Javo explains that he never loved Nora; he really needed her when he came back from Thailand, but he’s starting to feel better again. A tear slides down her cheek. “Come on, mate, we can outlast the lot of them,” he says. “We see so little of each other, we’re bound to,” she says, as if that’s the point.

In another room Nora’s housemate sits on the bed, playing guitar in his yellow socks and Volleys. He knows Javo is there but he’s being tactful about it. Later, they all go to a party. Life happens around them. A woman at the party observes that men do not like liberated women. People meet for quiet chats by a trellis adorned with green lights. And then the awful moment: someone’s crying in the dark over a can of Fosters and it turns out, incredibly, they’re crying about you.

It’s Lillian, and she’s now read Nora’s published story, the one she decided not to tell Lillian about. “Events don’t belong to people,” Nora explains. But everyone knows who the characters are, Lillian argues. “Twenty people in Carlton do not constitute everybody!” says Nora.

Lillian accuses Nora of just publishing her diaries – a critique that famously dogged Garner at the time, as if, she wrote in an essay in 2001 and was still telling Claudia Karvan in an ABC special 20 years later, writing diaries isn’t an interesting, challenging, valuable thing to do. But there’s no time for that discourse; Javo is inside, and look – he’s thrown up on himself again.

“Sorry, Nor!” he says. “Guess the dope’s fucked me liver.”

“Don’t be sorry, people have had to do this for me heaps of times,” she fibs, as she picks him up and hauls him away from the party.

Her housemate goes on tour. She rides her bike; she thinks. She drops a letter round to Lillian’s: “Can you see this gets to Javo?” She keeps riding her bike – one of the skills Hazlehurst had to learn for the film; the other, she told Women’s Weekly, was swimming – and soon she’s at her old share house, where lovely Clive still lives. She cries in his arms. She cries in the arms of a woman she hasn’t met. She leaves the house and cries again in front of the cast-iron fence. Was this scene filmed in Melbourne? Again, if not, it’s a pretty good fake.

Ash29/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

And now we’re back at Fitzroy Pool, and it’s summer again. In the DVD commentary, Alice Garner points out that the scenes at the pool, which were filmed at Ryde Aquatic Leisure Centre, have done the trick for any Melburnian who’s seen the film, and even Cameron says he’s “quite proud” of the recreation. (When I watched it, I took it as self-sighted gospel that the bleachers at the Fitzroy Pool used to be blue on the verticals.)

Rachel Ang, whose 2018 comic Swimsuit was set at Fitzroy Pool, told me they set the comic there because “it’s really an amphitheatre, this stage for all kinds of emotional drama”. Ang, who is also an architect, was struck by the “formal power” of the space where the sun acts as a spotlight and shines on “everything”, the dramas and their social implications.

Victoria Hannan, whose 2020 novel Kokomo also has a critical scene set at the pool, told me that she did so as a “direct tribute” to Monkey Grip – the scene in the novel where Nora tells Clive, “No-one will understand but this is a paradise.”

I wanted to spend this time with the plot of Monkey Grip because I wanted to try to see, if I could, the thing itself. By the end of the movie, what’s obvious is that the thing itself extends beyond the characters and past the movie’s frame, into the rich shine of the sunshine, the blue soak of the pool.

There are fabulous clothes (Nora wears everything from a fuzzy tangerine sweater to a pair of pedal-pushers in animal print; even Martin, at one point, wears a denim jacket and rope-net shirt). It’s the yeahs, give-it-a-burls, fair-dinkums, I-think-it’s-beauts; a song done well at band practice is described as “very tasty”. It’s the slowness, the detail, the gossip, the repetition. Everyone’s always smoking in front of louvres that are always smudgy, and though the men may look unfathomable, they’re also always there.

At the pool, Nora gossips with another old housemate. Gracie gossips at the water’s edge with the old housemate’s kid. Javo is at the pool, under the AQUA PROFONDA sign. Nora approaches him in possibly the best outfit of the film, a red cap and lemon bomber over a one-piece bathing suit. It makes her happy that Javo’s doing well, but it’s bloody painful, too. It’s like watching a kid grow up and take off. She liked him needing her.

“Mate,” Javo says. “Our relationship’s permanent. Maybe we could go out tonight or something.” But she’s seeing a movie with Gracie. She remembers him the summer before, and it makes her reflect on their world,

how we thrashed about, swapping and changing partners, like a complicated dance to which the steps hadn’t quite been learned, all of us somehow trying to move gracefully, in spite of our ignorance.

A beautiful score rises, quite heavy with strings. Everything is blue. The credits rise. The movie ends.

This essay is extracted from Melbourne on Film: Cinema That Defines Our City (RRP:$34.99), which is published by Melbourne International Film Festival and Black Inc.

Monkey Grip will screen at MIFF on Sunday 14 August.