Along with his friend François Truffaut and several other future directors, Godard had been writing devastating put-downs of the current state of the official French cinema in the magazine Cahiers du cinéma. At the same time, they devoured the Hollywood westerns and thrillers which were circulating freely in Paris and spent long evenings at the Paris Cinémathèque.

They tried out their ideas in short films. And then, between 1958 and 1960, one after the other, they released their first feature films. The effect was immediate. Truffaut won the Golden Palm at Cannes in 1959 for his autobiographical The 400 Blows. Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour narrowly missed that prize. At the end of the year, Godard released Breathless.

In it, Jean-Paul Belmondo (who was not yet a star), and Jean Seberg (who was), are two lovers on the run from the police on the streets of Paris, seeking money to escape the city. It was energetic, stylish and surprising, full of unexpected digressions and imaginative shots that brought Paris to life on screen.

Catching the cultural mood

For the next decade, Godard would cement his reputation as a director with his finger on the pulse of modern life. Sensitive to the debates and discontents of the decade, he took storylines from the American genre films he loved and used them as frames on which to attach glimpses of a changing France, satirical sketches, adverts, and quotations from theorists, poets and political protesters.

In Alphaville (1965) he makes the popular serial hero Lemmy Caution break down the system of a machine-run future city by means of a book of poetry. In Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967), he turns a day in the life of a part-time prostitute into a summary of the condition of Paris, in less than 90 minutes.

Between 1960 and 1967, Godard made 15 feature films. Each one sparked debate among an enthusiastic, largely young audience who felt that he spoke for the times. They were quite happy – in fact, delighted – to accept that the films weren’t always easy to follow. The cultural explosion of 1968 was brewing; student protests and worker strikes were challenging the French (and European) status quo. Godard’s prickly, fragmented cinema seemed to be asking all the right questions.

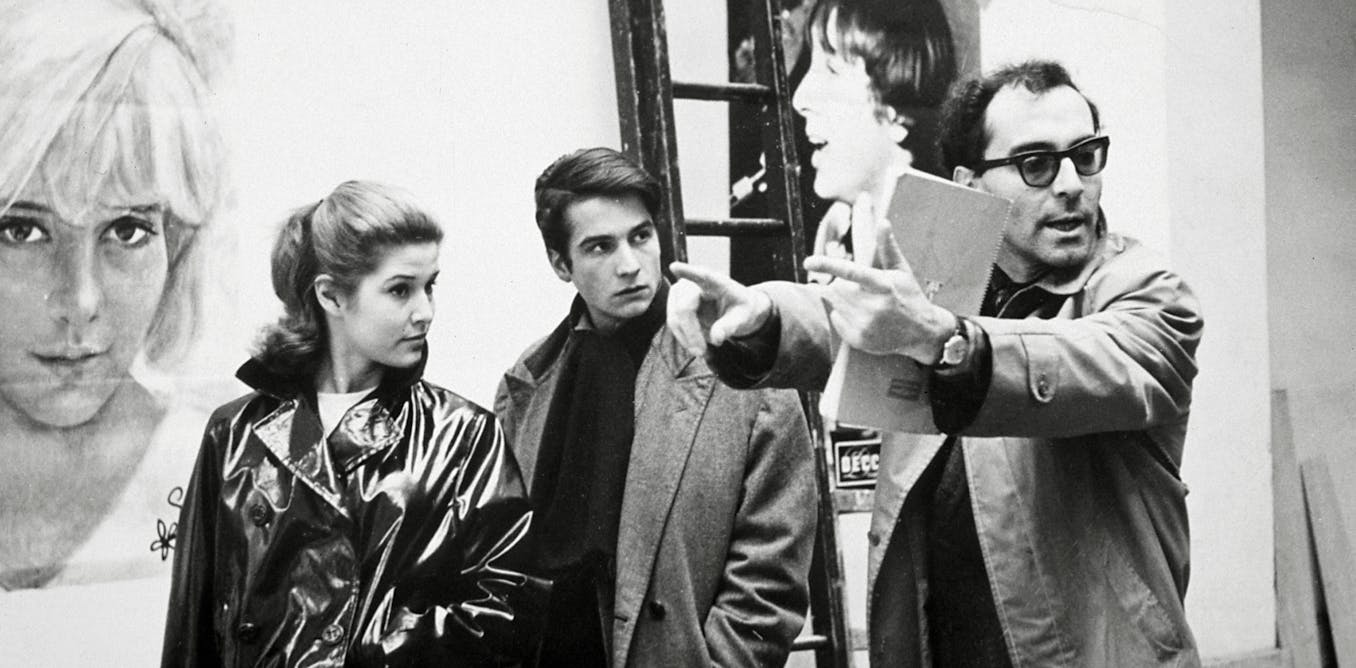

Science History Images/ Alamy

In the aftermath of 1968, everything changed. Swept up in the radical political rhetoric of the time, Godard announced his withdrawal from mainstream cinema.

His bitter falling-out with François Truffaut marked the end of any possible illusion that the New Wave still existed as an entity. He and some friends formed a short-lived experimental collective, the Dziga-Vertov group. It only lasted three years, but Godard remained largely absent from commercial screens for a decade.

A new direction

Not that he had stopped working. He experimented – with the new medium of video (Numéro Deux, (1975)), with political activism and television work. He cemented his professional and personal partnership with Anne-Marie Miéville, which was to last the rest of his life.

In 1981, his first new feature film for a decade, Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie) (Every Man For Himself), co-written by Miéville and starring Isabelle Huppert, marked a return to the forefront of critical attention.

The “new” Jean-Luc Godard was no less experimental, challenging or spiky than the old one had been. Audience expectations, however, had changed, and he was never to regain the status of popular youth icon that he had held in the 1960s. Instead, he developed a reputation as an awkward thinker, but one who illustrated his ideas about cinema and politics in sound and image, rather than explaining them in books and articles.

He and Melville had moved their production company to the small Swiss town of Rolle in the late 1970s, and as he grew older, he became more and more unwilling to travel away from that base – as over-optimistic festival directors who found themselves “waiting for Godard” can attest. He appeared in his own films as a chaotic, cinema-obsessed recluse (First Name: Carmen (1983), and King Lear (1987)).

Everett Collection Inc / Alamy

But he and Miéville worked continuously. Film after film proved their commitment to research and their refusal to compromise. The monumental History/ies of Cinema (1989-99) is still a challenge to received ideas about cinema’s place in history and the historical role of images.

The political anxieties of the new millennium, from persistent wars on the edges of Europe to the dialogue between the global north and south, find their restless way into films like Notre Musique (2004), Film Socialisme (2010) and his last feature, The Image Book (2018).

It’s not all that easy to make out exactly what he wants to say about these things, let alone agree with him. But then, Godard never showed much sign of expecting agreement. His vocation was as an irritant, and long may his exceptional filmmaking remind us of that.